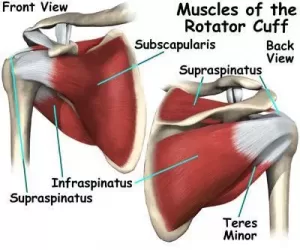

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles that serve to dynamically stabilize the

When working with shoulder issues, proper exercise selection targeting the rotator cuff and surrounding accessory musculature is imperative. The rotator cuff muscles originate on the scapula; therefore, establishing scapular stability is critical to provide the rotator cuff muscles a stable base from which operate.[2] In this blog, we will break down the research on each rotator cuff muscle to help you better understand and improve your exercise selection.

Supraspinatus

The main function of the supraspinatus is to compress, abduct, and (slightly) externally rotate the glenohumeral joint.[1] In the plane of the scapula, the supraspinatus generates the greatest amount of abduction torque; therefore, exercises in this plane are ideal for strengthening the supraspinatus.[1] EMG data suggests using the following exercises to target the supraspinatus: full can in the scapular plane; prone T at 100 degrees of abduction with ER; and prone full can (Prone Y).[1]

Infraspinatus

The infraspinatus is located on the posterior side of the shoulder, and its main function is twofold. First, it compresses the humeral head into the joint, preventing it from sliding around. Second, it externally rotates the shoulder.[1] Thus, the best exercises for the infraspinatus typically focus on external rotation. EMG data has demonstrated that at lower angles of shoulder abduction, the infraspinatus is more effective at externally rotating the shoulder.[1] A recommended exercise for the infraspinatus is side lying external rotation.

Teres Minor

The teres minor is also located on the posterior side of the shoulder and works with the infraspinatus to compress the humeral head and externally rotator the shoulder.[1] Due to its orientation, the teres minor is better able to produce a consistent amount of torque throughout the range of shoulder abduction.[1] Some of the most effective exercises for activating the teres minor include: side lying or standing ER at 45 degrees of abduction; and prone ER at 90 degrees of abduction.

Note: With positions of increasing arm abduction, the amount of EMG activity in the infraspinatus and teres minor will decrease as the deltoid and supraspinatus kick in.[1] This information becomes critical when dealing with post-operative situations, but we will touch more on that later!

Subscapularis

The subscapularis also compresses the humeral head, but furthermore, it internally rotates the shoulder and provides anterior shoulder stability.[1] At 0 degrees of abduction, larger muscles such as the pec major, latissimus dorsi, and teres major assist the subscapularis with internally rotating the shoulder.[1] Therefore, recommended exercises for the subscapularis include IR at 0 degrees of abduction, IR at 90 degrees of abduction, and D2 PNF flexion/extension.[1]

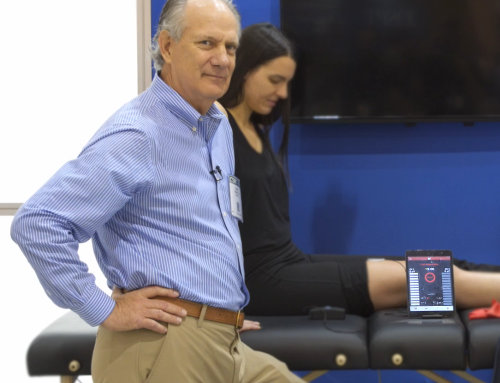

Due to its location on the underside of the scapula, the subscapularis is difficult to accurately access with surface EMG biofeedback. Studies looking at subscapularis muscle activity typically use indwelling EMG to gather data. While mTrigger is not an indwelling EMG device and therefore cannot measure subscapularis activation directly, the best exercises for targeting this rotator cuff muscle should still be widely utilized in rotator cuff treatment.

Zooming Out

When selecting exercises, understanding the EMG activation levels of different muscles surrounding the scapula is important. The deltoids, serratus anterior, and lower trapezius are three examples of scapulothroacic muscles that should be included in a rotator cuff rehabilitation program because of their direct impact on the movement of the shoulder.[1] This impact is important. During the standing full can exercise for example, the middle and posterior deltoid have relatively low levels of activation.[1] In the prone T and prone Y exercise, however, the EMG levels of the middle and posterior deltoid greatly increase, increasing humeral head motion, which can be detrimental when rotator cuff pathology or post op healing is present.[1,3] This is why understanding the effect and EMG levels of exercises focused on the shoulder girdle is so important.

Deltoid

The anterior, middle, and posterior deltoid muscles are active during several common exercises, with some exercises targeting more specific heads of the deltoid.[1] High activation of the middle deltoid results in superior humeral head migration, which isn’t always ideal for dynamic stability and joint congruency.[1] Posterior deltoid activation on the other hand, does not lead to humeral head migration, and in fact aids in rotator cuff and shoulder joint stability.[1] The prone Y exercise exhibits a high level of posterior deltoid EMG activation.

Serratus Anterior

The serratus anterior works to protract and upwardly rotate the scapula.[1] This muscle is a driver of proper scapular movement during arm elevation and helps to prevent scapular winging by stabilizing the medial border and inferior angle of the scapula.[1] To really focus on serratus anterior activation, EMG data suggests utilizing exercises such as: the dynamic hug; push up plus; serratus punch at 120 degrees elevation; and wall slides.[1]

Lower Trapezius

Finally, the lower trapezius serves to upwardly rotate and depress the scapula, with certain fibers aiding in posterior tilt and external rotation during arm elevation.[1] As the shoulder moves from 90 degrees to 180 degrees of elevation, the activation of the lower trap increases significantly. For this reason, the prone Y; prone ER at 90; and prone horizontal abduction at 90d degrees with ER have the highest EMG activation of the lower trap. [1]

Summary

Exercise selection is critical when addressing deficits in the rotator cuff and surrounding scapulothoracic musculature. EMG data helps clinicians construct a good rotator cuff program that incorporates exercises targeting a stable scapular base and normal glenohumeral kinematics.[2] Furthermore, once the ideal exercise is selected, the use of mTrigger visual sEMG biofeedback can further enrich a patient’s ability to achieve highly accurate and effortful muscle activation.

Check out our electrode placement guide and give the exercises above a try with your next rotator cuff patient!

mTrigger Biofeedback for Gluteus Medius Weakness

|

Subscribe to our E-mail list

|

References

[1] Reinold MM, Escamilla R, Wilk KE. Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther [Internet]. 2009;39:105–117. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19194023/.

[2] Ganderton C, Kinsella R, Watson L, et al. Getting more from standard rotator cuff strengthening exercises. Shoulder Elb [Internet]2020;12:203. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32565922/.

[3] Alizadehkhaiyat O, Hawkes DH, Kemp GJ, et al. ELECTROMYOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF SHOULDER GIRDLE MUSCLES DURING COMMON INTERNAL ROTATION EXERCISES. Int J Sports Phys Ther [Internet]. 2015;10:645. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26491615/.

Leave A Comment